She wasn’t the best dancer. She wasn’t the best singer. She wasn’t the most beautiful. (Though she scored high in all those categories.) Still, nobody ever enjoyed singing and dancing and looking beautiful more than Mitzi Gaynor, who died recently at the fine old age of 93. Mitzi, whose name and personality almost demand an exclamation point, wore sequins and spangles like a second skin as she practiced a particularly vivacious form of mid-century show business song-and-dance. With her perfectly proportioned body (tiny waist, slim but shapely legs, pert tush, lush bosom) she was like a Barbie doll brought animatedly to life. She seemed to get the joke: that it was all dress-up fun and not to be taken too seriously. That edge––call it camp, I guess, though I didn’t know it at the time––comes through loud and clear in this clip from Ed Sullivan’s TV variety show on February 16, 1964. Oh yeah, the Beatles were on the same show, but I couldn’t have cared less. I was mesmerized by Mitzi and her “boys” as they sashayed through “Too Darn Hot” on the same show, she flouncing her skirt up and the boys swiveling in their tight pants.

The Hungarian dancer (real name: Francesca Marlene de Czanyi von Gerber) relocated with her family from Detroit to Los Angeles as a child. She was in ballet class from an early age and on the professional stage by 13, dancing in operettas presented by L.A.’s Civic Light Opera. She was signed by Twentieth Century-Fox, had her name changed from Gerber to Gaynor (after early Fox star, Janet Gaynor), and made her film debut while still a teenager in the 1950 Betty Grable vehicle, My Blue Heaven.

Mitzi was clearly being groomed as a new era Fox blonde in the mold of Grable when she starred in a series of mild musicals in the early 50s. But she hit a couple of speed bumps in the process. Films like Golden Girl (1951), Bloodhounds of Broadway (1952), and Down Among the Sheltering Palms (1953) didn’t make much of an impression at the box office, and her big star vehicle, The “I Don’t Care” Girl (1953), a biopic about vaudeville sensation Eva Tanguay, was a choppy mess. At least she got to work with choreographer Jack Cole, who placed Mitzi in the center of some of his most flamboyantly abstract numbers. In the title song, she’s a siren in ostrich feathers who beats back both a block of menacing men in black and a phalanx of women’s temperance marchers (including co-stars David Wayne and Oscar Levant in drag), all while dancing through fire, water, and a train wreck in a number that strains the confines of a soundstage, let alone a vaudeville stage. Again, Mitzi got the joke and performed it like the camp hoot it was, and still is.

The biggest impediment to Mitzi’s position at Fox was another new blonde, Marilyn Monroe. When she and Monroe both appeared in the Irving Berlin songfest, There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954), it turned out to be Mitzi’s last film for the studio. As the dancing daughter of Ethel Merman and Dan Dailey in the garish, maudlin saga of a vaudeville family’s romantic and career travails, she was both the sanest of the clan and a knockout comedienne. Mitzi was not the musical sweetheart Fox wanted, but a boisterous dancer-singer possessed of a camp knowingness, one who could vamp with the best of them and hold her own alongside “the Merm.” They really do look like they could be mother and daughter barreling through the silly “A Sailor’s Not a Sailor (‘Til a Sailor’s Been Tattoed).”

The film also gave Mitzi her most simpatico dance partner in Donald O’Connor. With O’Connor playing her brother, they could dispense with romance (O’Connor was Monroe’s improbable love interest) and get down to some roughhouse hoofing, especially in this knock-out number parodying their parents’ early vaudeville act.

Mitzi’s biggest film hit, the one that headlined all her obituaries, was Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific (1958). Ironically, as Navy nurse Nellie Forbush, her natural ebullience was tamped down. Work uniforms and shorts and blouses just didn’t seem natural on Mitzi. As her film career slowed, her husband/manager, Jack Bean, helped her launch a stage career that lasted more than three decades. Theirs was a familiar kind of show business marriage, with the husband taking charge of his wife’s career. See Ann-Margret and Roger Smith and Carol Channing and Charles Lowe. None of these marriages produced children; the wife’s career was the blessed event, the focal point of their combined efforts.

As a star headliner in Las Vegas and nightclubs around the country, Mitzi was a natural, revisiting numbers from her films, telling jokes and doing impressions (she was a wicked mimic), and displaying her undervalued acting chops. A highlight of her early act was a character she called “The Kid,” a precocious little pisher in baseball cap and dungarees who slowly revealed affecting traces of loneliness and isolation. From the start, Mitzi was always surrounded in her act by a tight group of worshipful male dancer-singers. In a way, she created the template of the Glamorous-Lady-Star-and-Les Boys act that was revisited by everybody from Ann-Margret (with younger, more smoldering boys) to Chita Rivera (harder-edged and more Broadway).

Mitzi occasionally popped up on TV, but it was her performance on the Academy Awards broadcast in 1967 that jump started a new wave of TV appearances. She was at her Mitzi-est singing and dancing to the Best Song nominee, “Georgy Girl,” first in a dowdy smock and glasses, then metamorphosing into a dazzling “go go” Mitzi, carried aloft by her ever-present boys. (Let’s pause to acknowledge those boys: Alton Ruff, Carl Jablonski, Birl Johns, and Lee Roy Reams.) This Vegas-y version of the lilting song gave TV audiences a taste of the kind of high strutting act that nightclub audiences had come to expect.

Mitzi soon began a series of annual TV specials that ran through the end of the 1970s. This was the heyday of musical-variety specials as highly anticipated, event programming. Mitzi’s specials were like mini-MGM dance musicals, and she worked closely with a trusted group of choreographers: Robert Sidney (who staged her early club acts), Danny Daniels, Peter Gennaro, and most often, Tony Charmoli, who also directed many of the shows. The star was front and center in comedy sketches (many of which haven’t aged particularly well), dramatic song solos, and lots of big production numbers––all extravagantly costumed by that master of sartorial glamor, Bob Mackie. Who wore it best? Mitzi, of course! Cher, Carol Burnett, Diana Ross, Barbra Streisand––they may have been bigger stars, but no one enjoyed flaunting it in Mackie like Mitzi.

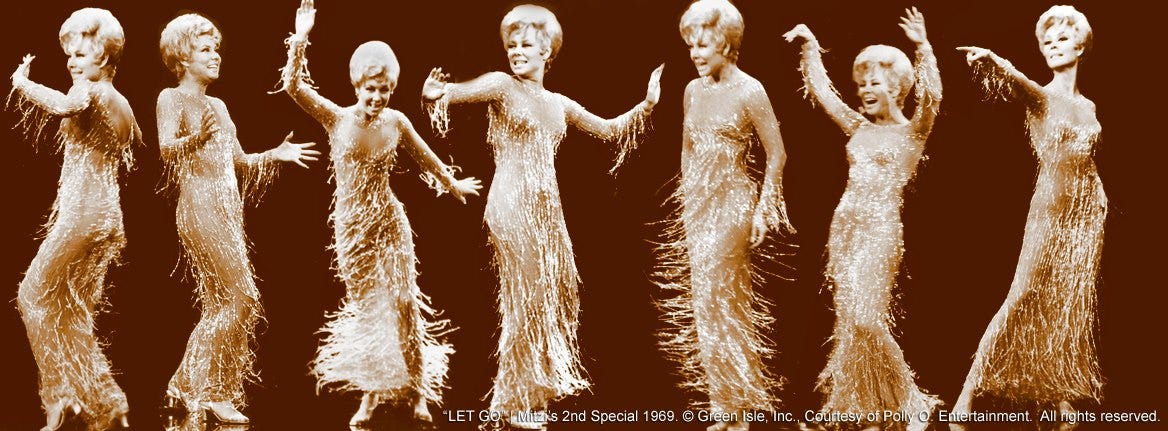

The greatest “Mitzi to the Max” moment is “Let Go,” the opening of her 1969 special. This jaw-dropping sequence, performed on a black lacquered playing area supported by what looks to be giant icicles, features eight handsome, tuxedo-clad men (a friend of mine referred to them as The Mart Crowley Dancers) in support of Mitzi sporting the ultimate Mackie gown. His “nude illusion” dress is a contemporary gloss on similar gowns Jean Louis designed for Marlene Dietrich in the 1950s. The sheer, flesh-colored fabric drips with strategically placed bugle beads that take on a life of their own when Mitzi starts swingin’ to this samba-like sizzler. In design, performance, and photography there was nothing quite like this on 1969 TV. The circling camera movements that isolate Mitzi and company in a pitch black vortex, the men’s appearance out of the darkness to join her before disappearing, the hypnotic frug-like choreography, the chugging musical arrangement that winds itself down to basics––more than a half century later the atmosphere and presentation of “Let Go” gives off an avant garde feel. And leave it to Mitzi to add the perfect coda, (tastefully) shaking her moneymaker to a cowbell as she walks away from the camera. It’s a number for the ages.

Her stage act, rebranded as The Mitzi Gaynor Show, continued criss crossing the country from Atlantic City to summer tents to theaters in the round. In a 1982 New York Times interview during a week’s engagement at the Westbury Music Fair on Long Island, New York, the 51 year-old star discussed being on the road as much as eight months at a time, then kicking back with her husband for the remainder of the year.

Eventually, in the 1990s, she came off the road. After Jack Bean died in 2006, fifty-two years after they were first married, Mitzi put together a more intimate club act called Razzle Dazzle! My Life Behind the Sequins. Audiences expecting a revealing Lena Horne-Elaine Stritch-style career summation instead got a dishy, anecdote-filled revisiting of her film experiences and the various stars she encountered––all with multiple Bob Mackie costume changes. Mitzi, now hitting the 80 year mark, was still sunny, still upbeat, and full of good-naturedly risqué stories delivered with a wink.

Despite her longevity and accomplishments, perhaps what’s most interesting about Mitzi’s career is not what she did, but what she didn’t do. She and Jack Bean preferred to limit her to a couple of lanes from which she almost never strayed––even into territory that might have welcomed her. After the specials started, she mostly stayed away from other TV appearances. There were no sitcoms, no TV movies, no talk shows, no award shows, no guest shots on other stars’ specials. Likewise, her stage appearances were limited to her own shows. With the exception of playing Reno Sweeney in a tour of Anything Goes in 1989, she never headlined in Hello, Dolly! or Mame, two shows that, by personality and skill set, she was perfect for. She never sang “I’m Still Here” in a production of Follies. Her flair for bawdy humor was never tapped for character parts in movies.

What she did do in her later years was serve as a delightful interview subject on television and in special live appearances. Mitzi, eyelashes in place, was always ready to reminisce about South Pacific and offer stories about, and impersonations of, Ethel Merman and Marilyn Monroe. The gayer the audience, the more outrageous the performance, as in this 2008 interview conducted by Bruce Vilanch at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco.

Now the show girl is gone. While most of her live performances are lost to time, her film work is still with us, to be enjoyed and appreciated by new admirers, demonstrating that she didn’t have to be the world’s biggest star to delight viewers across generations. Turner Classic Movie host Dave Karger got it right when he introduced a clip of Mitzi high stepping in There’s No Business Like Show Business and paused to add, “Take that, Marilyn Monroe!” Exactly.

Loved!